Love Story

The death of 28-year-old Sergei Grinkov was the final chapter in one of sport’s great romances.

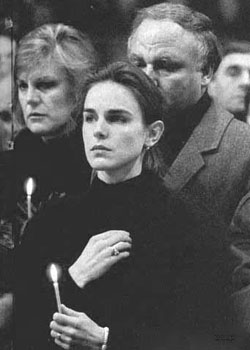

The tears came at Vagankovsky Cemetery last Saturday. Ekaterina Gordeeva had held herself together for most of this longest day of her life at the end of the longest week of her life--the performer doing her job, making other people feel at ease, no matter how bad she felt inside--but at the end there would be no control. The tears came, and she could not stop them.

Wrapped in the arms of the same Russian Orthodox priest who had married her to Sergei Grinkov only 4 and a half years ago, she cried and cried, cried for Sergei and cried for herself, cried at the realization that the words "and they lived happily ever after" were only words after all. What was it she had said to Skott Hamilton, the 1984 U.S. Olympic gold medalist and her friend? "Maybe everything was too good, too perfect. That was why it could not last." Maybe so...

On the gray Moscow afternoon, on this day she was supposed to be half a world away, previewing a tour in Lake Placid, N.Y., skating on a frozen cloud, looking into Sergei’s face, feeding off his strength as she always had, she was burying him in this cold Russian ground. The outpouring of grief had been constant since her husband had collapced and died in Lake Placid on Nov. 20, a 28-year-old victim of a coronary artery disease, and it was no different now. A Red Army band played the Russian national anthem. An honor guard fired a salute. The mourners, famous and not so famous, stood close. Viktor Petrenko, the Ukrainian gold medalist who had briefly led the funeral procession, still clutched Sergei’s picture to his chest.

Could anyone ever have more friends from more disparate places? Could anyone ever have better friends, friends and family who would do absolutely anything to ease Ekaterina Gordeeva’s pain? Could anyone ever be more alone?

She cried and looked very small and vulnerable in her black mink coat. She was 5’1" and 90 pounds and 24 years old and a widow. Could anyone know--really know--what had disappeared? If a depth of a sadness must be proportionate to the height of happiness, then there was not much lower that anyone could go.

"You could see the power that they had between them when they skated," Paul Wilie, the silver medalist from the 1992 Olympics and one of the U.S. visitors at the funeral, said. "Their eyes never left each other during the whole performance. No one else does that in pairs skating. It can be very distracting, looking into someone else’s eyes while you’re skating, but it never was for them. It was natural.

"You could just see how much they loved each other. You would watch them and just wish you had that sort of relationship with someone. We all wish we could find that kind of feeling, that perfect nuclear life. So few people actually do."

They were partners in the sweetest love affair in all of sports. They were a real-life Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Only better. No credits rolled across the screen at the end of their eye-pupping performance. No cameras and lights were broken down and taken to another place. The greatest pair in pair skating was a total pair, 24 hours a day, every day.

She was the dynamo, the sprite, flying through the air, spinning and twisting, part acrobat and part athlete, part prima ballerina and a whole lot of Tinker Bell. He was the hand in control of this spectacular yo-yo. Ten inches taller, stolid and smooth, he was the quite foundation to the act. He let her fly. He brought her back. The gasp of the crowd always came when Katya--her nickname--dropped close to the ice, her head only an inch or two away from serious injury. The relaxed sigh was the muted reaction when he did his job, brining her home safely again.

"They really are what pairs skating ought to be," John Nicks, a prominent U.S. coach, once said in describing Grinkov and Gordeeva at work. "They are the consummate pair. You can’t appreciate the capacity of a 180-pound man to move across the ice without a sound until you watch him skate. They are a symphony for the senses. Go to practice one day. Don’t watch them; just listen. Not a sound. No matter the ice condition, you hear only the music. They move so freely, their blades don’t scratch the ice."

Paired together somewhat reluctantly as children in Moscow under the old-line Soviet Union sports machine when she was 10 and he was 14, they grew up, fell in love, married and found freedom, all in public view. World champions when she was 14, Olympic champions when she was 16, they first performed as if they were brother and sister. They were a different sort of mismatched pair, able to use his strength and her tininess to create dramatic movements that had never been seen. They merged the artistic and the athletic.

"They proved that this kind of couple not only can work, but that this is the best way to do it," Stanislav Zhuk, one of Sergei’s first skating coaches, said, "At the beginning, everyone laughed. They showed them all."

Surprisingly they retired from amateur competition after winning their fourth world championship, in 1990. They rejoined Tom Collins’ Tour of World Champions, a troupe of amateur and professional stars, figuring they could skate for four or five years as professionals, make some money, then move on to separate, comfortable lives. But things happened. Plans changed.

First , they fell in love. Sergei , who had been dating other people, suddenly noticed in 1989 that the little girl who had been holding his hand all these years had become a woman. The little girl who had noticed Sergei for a long time, was more than ready for this change. They became as close off the ice as they were on the ice. They married in 1991. They had a daughter, Daria, a year and a half later. "I think it was on my tour when they first fell for each other," Collins said. "You could see it happen. It was all very sweet. They were with each other all the time. At first she was like this little rag doll that he threw around in the air, but she sure grew up. She became a beautiful young woman."

The change in skating rules for the 1994 Olympics in Lillehammer, making professionals eligible to compete, brought a second chance for the couple to win a gold medal. When they heard about the change there was little debate about whether to return. The children who won the gold medal in Calgary wanted to see what it would be like to win the gold as adults, as parents, in Lillehammer.

"Because I was so young before, I did not realize everything," Gordeeva said. "This time...I have a husband and I know my daughter watches me on TV. All this makes me more nervous, but more excited."

The result was all they hoped it could be. Of all the former champions returning from the pros, they were the only ones to repeat as gold medalists. Their routine to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata was quite magic, Grinkov measuring his strides to match Gordeeva’s shorter bursts. If he faltered slightly twice--singling a double Salchow and bobbling the landing on a double flip--the mistakes were more than overcome by the rest of the program. Eight of the nine judges put Grinkov and Gordeeva ahead of countrymen Natalia Mishkutenok and Artur Dmitriev, gold medalists two years earlier in Albertville.

The pair returned to the ice shows and found a new home in the U.S., in Simsbury, Conn. They already had bought a home in Tampa, but when plans were announced for international ice training center in Simsbury, and Peterenko and gold medal winner Oksana Baiul and other skaters and coaches from the Former Soviet Union started moving to town, this seemed to be a chance to combine the many pieces of a happy life. Gordeeva’s mother arrived to take care of Daria while the pair went on tour. Everyone was together.

"You’d see G & G everywhere around town," Jay Slovens, a publicist for the ice center, said. "They were always at the rink. In fact, they had just filmed a spot for a Christmas program to run on a local television channel. It’s set for December 3. There is this set of French doors, and G & G come skating through... I don’t know what’s going to happen with that now."

The "now" is what changed forever that day in Lake Placid. Sergei and Katya were practicing their routine. He had a bit of high blood pressure and had been bothered by a bad back that caused some numbness in his left leg, but otherwise he seemed in fine health. He was worried about some of the lifts that he would have to do when he and Katya went on the Discover Card Stars on Ice tour in late December. This was a chance to work on those lifts.

When Katya rushed from the rink in tears, asking for help, the other skaters thought at first that something must have happened because of Sergei’s back. Maybe he dropped Katya. Maybe he had hurt himself further. Maybe... it should have been so simple. He’d had a heart attack.

"He was blue," Wylie, one of 14 Olympians on the tour, said. "There was just nothing you could do except wait for the EMTs. I rubbed Katya’s back, and with my other hand I just touched Sergei’s skate. He was lifeless."

An autopsy showed that two arteries to Sergei’s heart were blocked and that he’d had an earlier, undetected heart attack in the last 24 hours of his life. There was a family history of heart disease, including his father, who died in his mid-40’s. Sergei basically had drawn an unlucky number from the genetic pool.

"Everybody took this so hard," Wylie said. "We’d all done this tour for a number of years. We were a family. This was where we came, lake Placid, every year for thanksgiving. We all just stared out at the lake."

Katya made the necessary arrangements in the middle of a holiday week in the middle of nowhere. She hosted a private wake at a funeral parlor in Saranac Lake and talked with friends and accepted condolences. Collins flew from Minnesota to Simsbury, to tell her that he would help in whatever way he could. Calls came from every where. Katya accompanied the body to Moscow, and on Saturday, at the ice rink that houses the Central Red Army hockey team and was the place where Sergei started skating, she sat through the funeral.

Wylie and Hamilton were there, and Bob Young, the executive director of Simsbury rink, was there, and a lot of other people were there, ordinary and famous. Russian people who had watched the unfolding of this romance that belonged to their country and also to the world. Katya was composed throughout the service. She always had been the spokesperson for the pair, the one in charge, especially in America because Sergei was shy with his English, and she was in charge here. And then she went to the cemetery. And then she cried for all there was and all there might have been.

Article by Leigh Montville. Photos Copyright © by Bill Swersey

Copyright © 1995 Sports Illustrated.